By Jim Daly, John Stewart and Kevin Woodward

An industry whose closest familiarity with viruses has come from the kind that infects computers has for most of this year had to contend with a pathogen that has sickened millions of people and killed hundreds of thousands. While the payments business is hardly alone in the sweeping adjustments it has had to make to contain the impact of the novel coronavirus, it is finding that a number of trends that were emerging pre-pandemic are now moving forward much more rapidly.

Indeed, some might now have such momentum as to be considered permanent.

Here, we consider six such trends. There may be a number of others, but these are the ones we have heard about most in our conversations with people in the business. Some, such as the moves to contactless payments and e-commerce, have gained understandable prominence in view of the urge to avoid infection and get shopping done under lockdown conditions.

Others, such as the impact on cash, illustrate ways that fear of infection can threaten payment methods that have survived through the centuries. And, as our reporting shows, crime in the form of payments fraud has rapidly made its own adjustments.

As we write this, the U.S. economy is fitfully reopening after long weeks in lockdown, and progress reports are arriving regarding a vaccine, though it may be long months before one becomes commercially available. All good signs, but it’s too soon to sound the all-clear klaxons. For the foreseeable future, fear of Covid-19 will remain a factor to be reckoned with. We here present how the pandemic has, for good or ill, affected some of the most fundamental currents in modern payments.

Cash To be Cashiered?

It seemed like cash, the epitome of up-close-and-personal payments, had become the Payments Public Enemy No. 1 as the Covid-19 pandemic raged this spring. Some news reports vilified cash as a medium that fast-tracked the highly infectious disease. A number toll-road and bridge authorities stopped accepting cash, and many merchants encouraged payment with anything but cash.

Credit-union service organization PSCU reported that, as of the week ending May 31, ATM cash withdrawals were down 30% or more year-over-year for ten straight weeks.

Government added to the public’s confusion about whether cash was safe. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidance for commercial establishments to practice good hygiene, in part by promoting tap-and-pay contactless payments “to limit handling of cash.”

But the U.S. Department of Homeland Security declared workers who service ATMs to be part of an “essential critical infrastructure workforce.” The Bank of Canada urged retailers to keep accepting cash to ensure consumers could buy needed products and services. “The risks posed from handling Canadian bank notes are no greater than those posed by touching other common surfaces such as doorknobs, kitchen counters, and handrails,” the central bank said in a news release.

David Tente, executive director for the U.S., Canada, and the Americas at the Sioux Falls, S.D.-based ATM Industry Association, isn’t too worried about cash’s long-term future. He acknowledges people haven’t had much need for it in recent months during lockdowns.

“I think cash is going to come out of this just fine,” says Tente, whose organization in June published its “ATM & Cash Revival Plan,” which includes continuation of its fight to ban cashless stores and development of ATM hygiene and safety protocols. “People still prefer cash in a lot of instances.” Tente adds that without cash, “You’ve got financial-inclusion issues” for people who don’t want or can’t get credit or debit cards.

Houston-based Cardtronics plc, the nation’s largest ATM owner, is betting its future on performing more tasks cost-conscious banks traditionally have done, such as directly operating ATMs. At a May investor conference, Cardtronics chief executive Ed West expressed confidence consumers will continue using cash.

“Cash at the point of sale has been declining for a long period time, but that’s primarily driven by an increase in the number of total transactions,” West said. Citing Federal Reserve data, West argued that “cash continues to be in the United States roughly 26% of the most frequently used consumer payments, so it still has a significant number of transactions that are out there.”

—Jim Daly

The Sudden Mainstreaming of Contactless

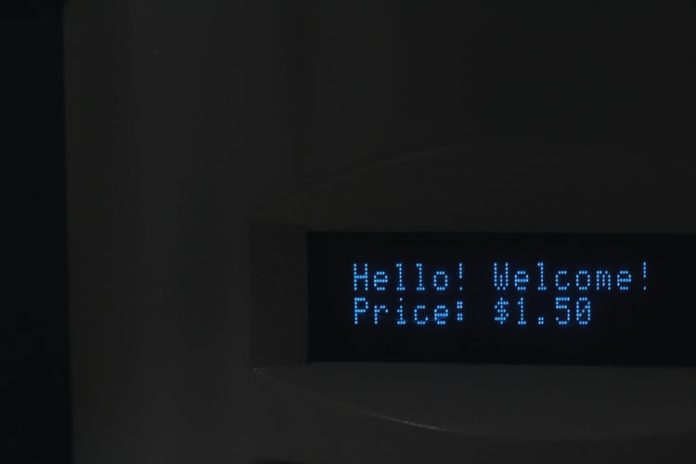

For years, the U.S. payments industry has talked about contactless payments. After this year, it may start talking about touch-free payments. Fearing infection, consumers have made it plain they don’t want to touch anything at the point of sale, not keypads, not pens, not even a proffered stylus to peck out a PIN.

But that contact phobia is also reshaping some traditional arrangements in payments.

For example, restaurant patrons are demanding apps that let them scan a code to call up a menu, place an order, and pay for the meal—all while they’re sitting at the table. In cases like this, the traditional card-present world is dissolving into the card-not-present space, says Ellen Linardi, head of product at Clover, a unit of Fiserv Inc. that makes point-of-sale payments technology (for more on POS trends, see Components, this issue).

It’s part of a broader definition of contactless, and it’s likely to long outlast the Covid-19 pandemic. “Trends like scan and pay, that is going to persist,” says Linardi.

To be sure, contactless payments have been available in the U.S. for years, and were making headway even before the pandemic struck. One big factor was the mass rollout of EMV technology, which lets card terminals read the EMV chip embedded in payment cards. Trouble was, not all merchants turned on the near-field communication capability in their new devices that lets them read the ultra-short-range radio signals from customers’ cards.

That’s changing fast. “We’ve been working with many customers lighting that up. I don’t think anybody is thinking they can operate without it,” says Chris Lybeer, chief strategy officer at POS device vendor Revel Systems.

In many cases the urgency has led to a clamor for contactless from merchants that still hadn’t installed the devices in the first place. “We’re seeing a lot of activity with existing customers. They want it now,” says Bradford Giles, senior vice president of marketing and sales enablement at Ingenico, a major POS terminal maker. “Before, they wanted to squeeze the last year or two of life out of what they had on the floor.”

Other vendors are seeing the same urgency, particularly as businesses reopen and merchants seek to soothe the anxiety of a fretful, mask-donning, social-distancing customer base. “Absolutely, folks are sticking this in right and left,” says Lybeer.

Look for variations on the contactless theme, some sources report, including renewed interest in NFC-based mobile wallets and some experiments with quick-response (QR) codes, popular in Asia, less so in North America. Also on the docket for some merchants is text-to-pay, another technology that lets users avoid touching anything at the point of sale.

—John Stewart

The Explosion of E-Commerce

Store shelves started emptying early this spring as multiple states adopted shelter-in-place rules, so consumers turned increasingly to online shopping to buy groceries, replenish household goods, equip their newly-created home offices, and get toys, games, and books to keep their children occupied.

The result? The Covid-19 pandemic has pushed e-commerce to the forefront for many.

E-commerce sales accounted for 11.8% of all U.S. retail sales in the first quarter, which only included a couple of weeks of the shutdown, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Until its next set of data arrives, businesses are providing insights into how the pandemic has altered e-commerce.

“We’re seeing growth in full-assortment grocery and click-and-collect, while general-merchandise merchants really have not been that successful in terms of growth rate,” says a spokesperson for Rakuten Intelligence, the San Mateo, Calif.-based data research platform of e-commerce powerhouse Rakuten.

Click-and-collect is a trend that is best positioned to have staying power beyond the Covid-19 crisis,” says Lisa Tadje, corporate communications, Rakuten Intelligence.

“Beyond the 130% year-over-year increase in click-and-collect orders we saw in April and the 123% increase we saw in May, we’re also finding an influx in new first-time click-and-collect buyers,” she says. “This lends itself to long-term success as existing users become increasingly engaged with the method and new users become accustomed as well.

Indeed, a new natural level of e-commerce may be in the offing, suggests a report from Signifyd Inc., a San Jose, Calif.-based fraud-prevention firm. Signifyd has produced a weekly e-commerce pulse report since March, when most non-essential retail shut down across the country. In its first report for June, the company’s data indicated a nearly 30% increase in e-commerce sales over its baseline, March 3-9.

Most verticals had increases in online spending in early June compared to early March. “In fact, of the 13 categories tracked by the Ecommerce Pulse, all but two—business supplies and beauty and cosmetics—are selling more online today than they were before the pandemic. The two down categories have suffered through much of the period of stay-at-home orders,” the report says.

Will these changes persist following the pandemic’s demise, whenever that comes? It’s hard to say. “While plenty goes into shifts in consumer spending, it will be interesting to see, as in-store shopping becomes more accessible, whether awkward Covid-19 shopping experiences will drive consumers back to online options for more purchases,” the Signifyd report says.

—Kevin Woodward

The Immediacy of Immediate Payments

History may record that 2020, the year of Covid-19, was the year that real-time payments proved their utility in the United States. From stimulus payments to peer-to-peer transfers, the need to get money into the hands of people with immediate needs was seldom more acute.

“I don’t think there’s any question that over the last 14 weeks we’ve seen a greater need to move money between people,” Michael Bilski, chairman of the Faster Payments Council and chief executive of North American Banking Co., told Digital Transactions last month. The council is a cross-industry group working on ways to stitch together a real-time payment network in the United States.

The emergency arose as millions were thrown out of work by business shutdowns, which helped control the rate of infection but triggered a deep recession. That left consumers in dire need of cash and made essentials, such as groceries, more frequent objects of transfers via real-time P2P systems like the bank-owned Zelle network. Zelle said in April it was already seeing a rise in paybacks to people for charities and groceries, as indicated by how users filled out the system’s memo fields. Zelle is operated by the bank-owned Early Warning Services LLC, Scottsdale, Ariz.

The U.S. market is late in adopting the immediate movement of money, which caught on in Europe and other regions years ago. But now it could catch up fast, thanks to the market’s experience during the Covid-19 emergency. “In general, businesses and consumers started to realize getting things faster is advantageous when a pandemic strikes,” says Bilski, who adds there’s now “a great need for safe, secure, and faster” payments.

Networks are moving to fill that need. The Clearing House Payments Co. LLC, a New York City-based operation owned by 24 big banks, early last month announced Huntington Bancshares Inc., Columbus, Ohio, was the latest institution to join TCH’s Real-Time Payments Network. Huntington is one of the 24 TCH owners. At the same time, the Federal Reserve is moving toward launching its own real-time system, called FedNow, within the next three to four years.

Issues remain, however. The FPC recently issued a white paper on the matter of interoperability, which means getting financial institutions to link to each other when they’re not all running the same systems. While enabling legacy batch systems to talk to newer real-time flows is part of the problem, Bilski says the larger issue lies in the looming need for seven-day weeks in back offices. “Are we all willing to do that?” he asks. ‘We just have to start migrating the change. It’s going to take some patience.”

—John Stewart

The Resilience of the Fraud Virus

Being a payments fraudster may be a pandemic- and recession-proof occupation. In good times, when all parts of the economy are open and consumer shopping is unimpeded, fraud activity is up. Now, as the Covid-19 pandemic proved, fraud activity is still rampant, just often in different ways.

It’s reasonable to assume that with the boom in online shopping and other digital transactions, fraud would spike in this area. Instead, LexisNexis Risk Solutions has seen physical identity-focused fraud attacks rise, particularly in new-account openings. But mostly what the company has seen are changes in behavior, says Kimberly Sutherland, vice president of fraud and identity strategy at Alpharetta, Ga.-based LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

“We definitely saw an increase in individuals transacting digitally more than before,” Sutherland says. A person might, when in the office, use a bank’s mobile app to check on her account, but when working from home, she might use a PC. “In general, digital-transaction growth was two times faster than we saw before.” LexisNexis Risk Solutions says new-device use increased nearly 40% in April compared to the average of January and February volume.

As more consumers adopt digital payments—a trend Sutherland suggests will continue—organizations will need to adapt their fraud-mitigation efforts. “As an organization they will continue to need to look at all channels a customer interacts with,” Sutherland says. “That concept of having an omnichannel experience will be very important.”

Information on scams may have broader appeal among consumers because so much more of the population is using digital channels than before. That’s the assertion from Ashley Town, director of fraud services at Co-Op Financial Services, a Rancho Cucamonga, Calif.-based credit-union services organization.

“Fraudsters found greater success in using … scams … during the pandemic because of its widespread impact to cardholders,” Town says. “Previously, when confusion would occur, it often was not something that a significant population was looking into. With Covid-19 having such a widespread breadth, we saw consumers across the country looking for information.”

And with the increase in online commerce, businesses that have not historically handled card-not-present transactions find themselves learning to do so at speed, says Rich Stuppy, chief customer experience officer Kount Inc., a Boise, Idaho-based fraud-prevention firm.

“Shoppers are requiring BOPIS—buy online, pick up in store, and BORIS—buy online, return in store, which presents potential for fraud that businesses might not have been prepared to address, especially with the speed of approvals that are required for a frictionless experience,” Stuppy says.

—Kevin Woodward

IoT Payments: Down, But Not for the Count

Locked-down Americans drastically reduced their driving in the spring, which naturally reduced demand for gasoline. Not quite so intuitively, reduced driving is also shaving Internet of Things payment volumes, according to David Nelyubin, a research analyst who monitors the IoT at Marlborough, Mass.-based Mercator Advisory Group Inc.

That’s because many consumers hoping to get lower auto-insurance premiums now have so-called telematics devices in their cars that feed all sorts of driving information to their insurers—and generate automatic IoT-based premium payments (“Wellsprings of IoT Payments,” May). But fewer miles traveled translates into fewer dollars paid in premiums, according to Nelyubin.

In addition, sales are down for such things as Internet-connected printers that track ink usage and automatically order and facilitate IoT payment for new ink cartridges, Nelyubin says. And if you’ve lost your job, do you really need an IoT electric toothbrush capable of tracking the wear on the brush head and ordering a new one, when a traditional electric model or manual toothbrush will do the job? Many payment-enabled IoT devices are still luxury goods that can be substituted for cheaper replacements.

“Overall, just from the virus, there is definitely going to be a decrease in IoT payments,” says Nelyubin, who predicts a 5% decline this year.

The long-term outlook is brighter. Nelyubin foresees 7% to 15% annual IoT payment growth in the next few years “depending on how the economy rebounds.”

Some of the growth will come from new IoT devices which, unlike their predecessors that facilitate payment between the device owner and only a single manufacturer or provider, enable the consumer to choose from an assortment of similar products from different vendors.

An example is the “Smart Feed Automatic Dog and Cat Feeder, 2nd Generation” device from Radio Systems Corp.’s PetSafe brand. The device, which looks like a coffee maker, lets the pet owner, using a smart-phone app, program the amount and time when food is dispensed into a bowl. Instead of being locked into one food brand, the pet owner can shop among multiple vendors and order refills through Amazon.com Inc.’s Amazon Dash Replenishment service.

Nelyubin says the PetSafe dispenser is the first consumer example he’s found of this new “open-loop” IoT model. “It’s really cool,” he says.

—Jim Daly